This is the newsletter version of Sara by the Season, where I explore what is piquing my curiosity as I try to lean into nature’s wisdom and rhythms. You can listen to me read you the newsletter by hitting play above - or you can click the little link above and to the right to play in your favorite podcast player. If you know someone who would like this sort of thing, I’d be so grateful if you would share it.

There’s a story about the Moken people, a native tribe that has lived on islands off the coast of what is now Thailand for centuries. Moken literally translates to “people immersed in water.” It is said their children learn to swim before they can walk. When the tsunami came in 2004, the Moken recognized the small signs that their elders had taught them about the “laboon.” Moken that were fishing at the time went farther out to sea; non-native fishermen were obliterated by the force of the tsunami. Despite their island being directly in the path of the wave and the tsunami killing an estimated 230,000 people in the region, virtually no Moken died in the tsunami because they knew - and listened to - their ancestral wisdom.

Llewelyn Vaughan-Lee says, “We have even forgotten how to read the patterns of the natural world, the meaning of the sunflower’s spiral, the shape-shifting clouds of a murmuration of starlings, or the sequences of change as the Earth warms. The natural world may be ‘the first book of revelation’ but because we have lost the knowing of how to read this book, we cannot see what is happening. Thinking in the images of science we miss so much that is sacred, how what is hidden reveals itself. Nor can we understand the present patterns that are unfolding around us. And so we are blind as we stumble into this future, where the stories of science and technology we believe can sustain us are written in a language that is part of this dying, that has helped to cause this crisis. And as we cannot recognize what is happening, we can neither dance nor dream. The sacred circle has long been broken.”

We have “lost the knowing” of how to read the natural world, and, in doing so, we’ve lost - or forgotten - the knowing of how to read ourselves; we aren’t apart from nature but we are nature. Most therapists, Instagram gurus, and pastors will tell you about the importance of knowing yourself, but very few of them talk about how we can’t really know ourselves separate from our interconnection with the beings we live with - human and more than human. A large part of our cultural dis-ease is our disconnection with the world we’re dependent on and entangled with.

We moved to our place eight years ago next month, and while eight years in a place is a minuscule drop in the bucket compared to the centuries native people like the Moken have invested in knowing their places, I’ve noticed that it’s taken me years to begin to notice patterns - and anomalies. Wendell Berry says that “it all turns on affection,” and while I think that’s certainly true, affection can’t arise without attention.

In an effort to recover “the knowing” and build my attention muscles, here are a few things I’ve been noticing and learning lately:

It’s weirdly dry for early summer. In the nearly eight years of learning this place, I’ve never had to water the garden this much this early in the season. We don’t water our “lawn” (really just a random mixture of grasses, clover, plantain, dandelions, wild violet, and other fun stuff), but it’s never been this brown this early. To be clear: I don’t really care that the “lawn” is brown; I’m just noticing that it is happening earlier than I can ever remember.

On the trail across the street where I walk, every morning Wendell and I walk through the sprinklers that water the manicured Kentucky bluegrass on either side of the trail, as well as most of the path. I wonder if the people that live in the neighborhood even realize that things are so dry since their grass is still so green (other than maybe their water bills are high?). If I didn’t have a garden that required tending, would I even notice?

The pollen is sticking around. I don’t usually get spring allergies, but Jasper does. I noticed he was sneezing a ton, and then the rest of us started getting that scratchy throat thing and sneezing all the time. Turns out, the warm winter across much of the country made this spring a particularly rough allergy season.

On our porch, I was sweeping up huge piles of what look like tassels1, but what I now know to be catkins - the male flower of the many oak trees that we have in our yard. They say the word “catkins” comes from an old Dutch word, katteken, meaning “kitten,” and how cutely appropriate is that? Catkins are the ways many varieties of trees and shrubs reproduce, so, in our oaks, the male catkins release their pollen into the air, and then drop to the ground, which is what I’ve been noticing everywhere. Eventually (hopefully), the pollen on the wind pollinates the female flower still on the oak tree, which then produces acorns. Supposedly, a high number of catkins means a mast year is coming. Mast years are boom years for trees, so, in our oaks, it means lots of acorns are coming this fall. Scientists say that mast years occur every 2-5 years, and even they aren’t totally sure why this occurs or what causes it.

My attention to my scratchy throat and sweeping up the stuff on the porch led to learning a cute new word and down the rabbit hole of a bunch of theories on why plants mast. Plus, now I’ll be on the lookout this fall to see if we have more acorns that usual.2

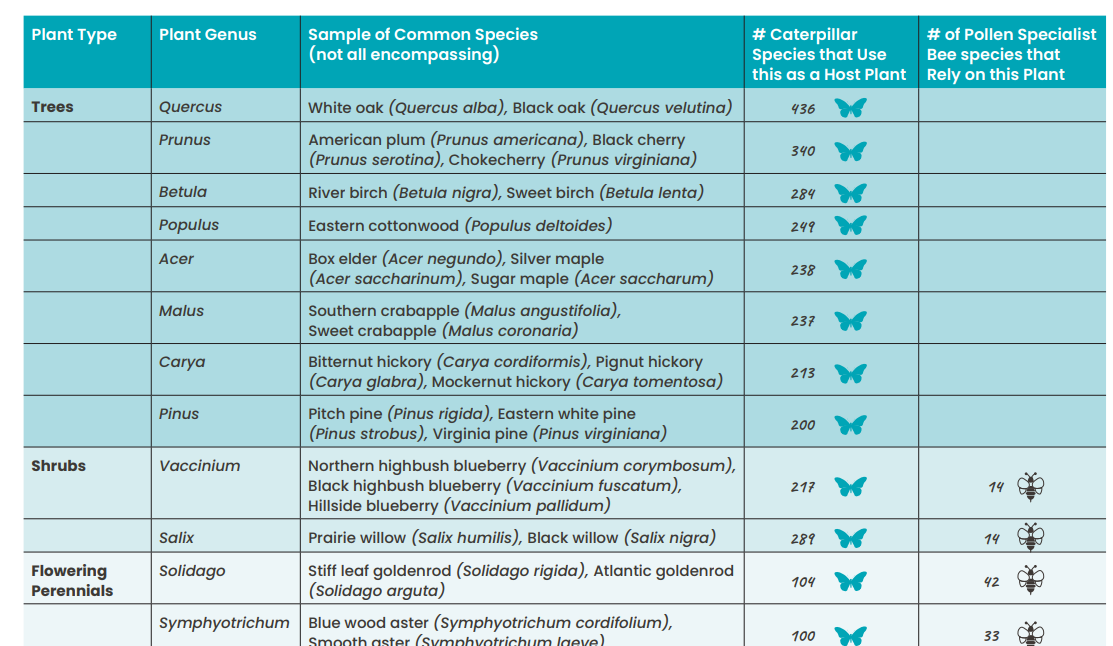

Keystone plants. I listened to - and really enjoyed - Nature's Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard by Douglas W. Tallamy. I wrote about keystone species here, but turns out there is a similar phenomena among plants. Much like keystone animal species that have an outsized impact on their ecosystems, keystone plant species have an outsized effect on the food web of their respective ecosystems. According to the National Wildlife Federation, “Keystone plants are native plants critical to the food web and necessary for many wildlife species to complete their life cycle. Without keystone plants in the landscape, butterflies, native bees, and birds will not thrive. 96% of our terrestrial birds rely on insects supported by keystone plants.”

These scientists got together and created a massive database by ecoregion of what are the most beneficial plants to plant in your ecoregion (this makes me ridiculously happy all by itself). Go here, find your ecoregion, and they rank the trees, shrubs, and plants by how many various species they support. So what’s been fun is to see how many keystone species we already have at our place - lots of oaks, maples, pines, perennial sunflowers, varieties of aster and goldenrod, a few willows, brambles, black eyed susans, coneflower, and more. But when I went to the nursery this spring to get more plants and trees, I took this list with me, so I could plant more keystone species and support much more life at our place. Now when I sit under the willow by the garden, I think about all of the life it’s supporting instead of just enjoying how it casts the perfect shade at all times of day.

Reading the so-called weeds. One of my go-to consequences for the kids in the spring time is to go dig up dandelions from the yard. Maybe this is not something to be admitting to, but I rely on them making dumb decisions to supply my dandelion root tea that I drink all year long. This spring, there were not nearly as many dandelions as usual. The presence of lots of dandelions tell us several things about the soil: mostly that it is acidic and compacted. We haven’t used any chemicals since we moved here nearly eight years ago, but it took at least several years to break the chemical-dependence from the previous owners. In that time, we haven’t done much to the “lawn” other than keep turning more of it over to forest, food production, or pollinators, to mow it high, and mostly leave it alone. Learning to read the “weeds” tells you plenty about your soil without having to wait to test it. We get lots of plantain where the chickens overgraze, which isn’t surprising because plantain tends to thrive in severely compacted soil and is a sign of acidic soil. Not only are most “weeds” either super nutritious, useful, or both, but it is helpful - and fun! - to learn how to spot them at your place, both for what they tell you about your soil and for deepening your attention to all of the life beneath your feet.

In an effort to recover the “knowing of the natural world” that Vaughn-Lee and so many of our indigenous elders advise us to do, the best place to start is at your own place. The smaller, the better. Our attention muscles need little and frequent victories. Pick one tree, bird, bird song, flower, or insect to learn how to recognize. Begin paying attention to how it changes throughout the seasons and even within the seasons.

What we give our attention to grows3. So we begin small, and that ability to notice grows. As our attention muscles get stronger, we find that we begin, slowly, to revive our knowing of the sacred, of our entanglement with one another and with the more than human world all around. James Bridle says that deepening our attention “makes everything really, really fascinating and interesting because there is always more to discover if you pay more attention.”

That sounds to me like a beautiful way to live.

Scattering Seeds

I’m always finding stuff that supports the thesis of the book I’m writing on the benefits of leaning into nature’s wisdom, as well as other things related to this newsletter’s topic that maybe didn’t fit into the actual newsletter, so I thought I could start sharing those links and things here with all of you in hopes of some of the seeds I share germinating into something beautiful at your place.

In hindsight, I think I’ve been listening to a lot of stuff lately that builds on this idea of bringing our attention in closer to the world right around us: James Bridle on On Being, Andreas Weber on Unknowing, and Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights (but please listen to it on audio - I now permanently have his voice in my head yelling, “delight!” whenever I notice something delightful and that alone is delightful).

I also listened to all of the episodes of Llewellyn Vaughn-Lee’s podcast, which was a beautiful spiritual practice over a few days.

This spring, I’ve been paying more attention to ever to the varied bird song outside our porch, but I really only know one or two bird songs. I’d liked to know more, and I’m using this as my guide. I don’t have a great ear for music despite loving it, and I find trying to learn the bird song so hard, but in a good way.

Science has a name for this concept of “what we put our attention on grows” called the Baader–Meinhof Phenomenon. Officially, it’s a logical fallacy that “occurs when something you recently learned suddenly seems to appear everywhere,” but we can use this knowledge about how our brains work to be wise about where we place our attention.

Here’s to deepening our attention in the smallest of ways closest to home,

Sara

I don’t even remember having to sweep them up in previous years, but Grant said that is because he usually sweeps them up. I love stories like this when people live together, and one person thinks something just happens or doesn’t happen only to realize the other person was doing it all along.

It also led me to this recounting of hazel catkins, which is a master class in paying attention and loving your place.

This seems to be one of those quotes that is attributed to many different people, but I heard it most recently from Adrienne Maree Brown.

Share this post